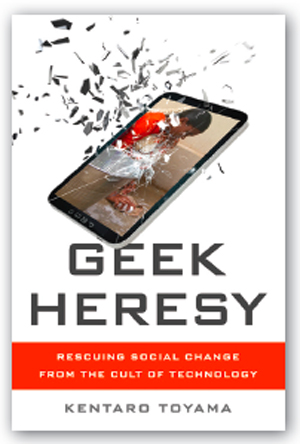

It’s a thin, superficial change.Īs an example of a project that has made a difference, your book cites Digital Green. Bringing along a laptop, connecting it to wireless, and providing Internet so you can do telemedicine is just an incredibly thin cover. If you go to a typical rural clinic, it’s not the kind of place that anybody from the United States would think of as a decent place to get health care. Bangalore was being described as the next great tech hub.Īnother example is the health-care system. When you went to India, technological optimism was flourishing there. Toyama, who is now an associate professor in the School of Information at the University of Michigan, spoke to MIT Technology Review’s deputy editor, Brian Bergstein. In a book being released this spring, Geek Heresy: Rescuing Social Change from the Cult of Technology, Toyama argues that technologists undermine efforts at social progress by promoting “packaged interventions” at the expense of more difficult reforms. But early successes in pilot projects often couldn’t be replicated in some schools, computers made things worse.

He and his colleagues launched dozens of projects that sought to use computers and Internet connectivity to improve education and reduce poverty. After getting his PhD in computer science and working on machine vision technologies at Microsoft, Toyama moved to Bangalore in 2004 to help lead the company’s new research center there. Kentaro Toyama calls himself “a recovering technoholic”-someone who once was “addicted to a technological way of solving problems.” Five years in India changed him.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)